In Her Own Words: Mary Wollstonecraft’s Letters from Bath (1779-1781)

While working as a companion in Bath in her early twenties, did Mary Wollstonecraft meet a mystery man?

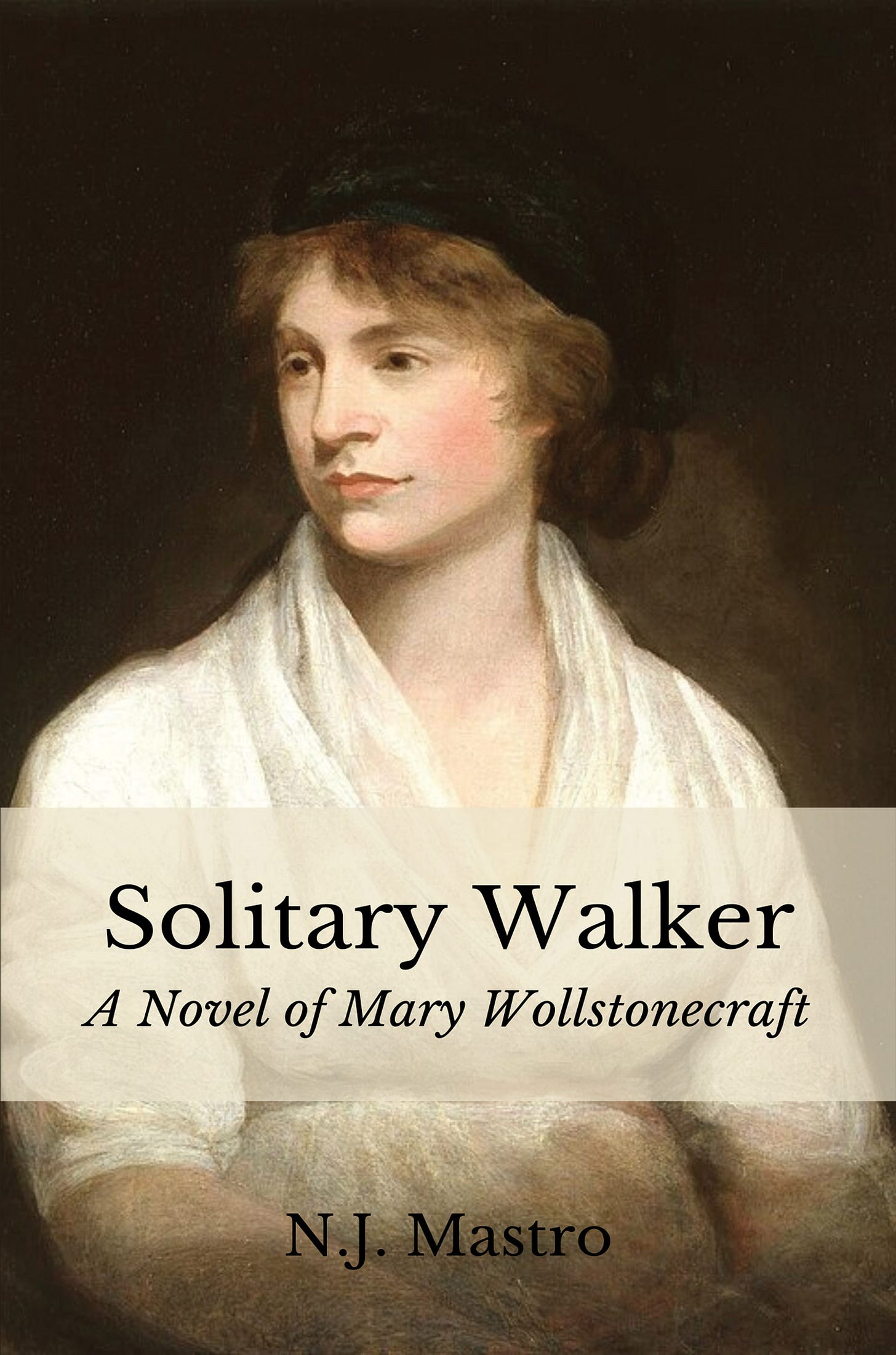

I’m the author of Solitary Walker: A Novel of Mary Wollstonecraft. Told against the backdrop of 18th century London, the French Revolution, and the remote shores of Scandinavia, Solitary Walker is the timeless story of a woman forging her own path in a man’s world.

When young people venture into adulthood in search of their dream, they are bound to encounter obstacles. And they carry with them the baggage of their youth. The path is even more challenging for individuals striving to escape poverty and break free from a tumultuous upbringing marred by family issues and mistreatment. Neither deterred Mary Wollstonecraft, the woman considered the mother of feminism, but she lived with the scars of childhood her entire life.

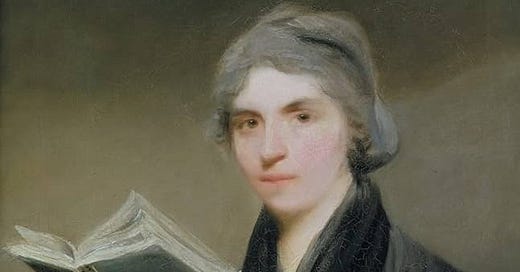

In 1779, 19-year-old Mary left her parents' London home to become a companion to Mrs. Sarah Dawson, a wealthy widow who spent time between Bath and Windsor, depending on the season. Mary (an early image below, c. 1786) had been seeking a position for some time. Her father, Edward Wollstonecraft, had squandered the family fortune. A violent man, he abused his children and assaulted his wife sexually. Mary grew up loathing him, believing men, by their very nature, held the potential to act similarly. Thus, at an early age, she rejected the institution of marriage, deeming it male subjugation, which coverture laws ensured.

Because of strict societal rules, as a middle-class woman, Mary’s employment options were limited to being a companion, a teacher, or a governess, none of which appealed to her. But Mary was a realist. Desperate to save money so she and her dear friend, Fanny Blood, could create a household together, she traveled one hundred miles by coach to arrive in Bath in the spring, where she promptly delivered herself to Mrs. Dawson’s house on Milson Street.

The home was close to Bath’s legendary shopping district, placing Mary in proximity to shops and sights that most young girls would envy. As a popular resort town famous for its healing baths, Bath was the place to see and be seen, perfect for finding a husband. Sightings of aristocrats and royals during high season were a matter of routine in this relaxed atmosphere, where members of the middle and the upper classes mixed casually.

Mary wanted none of the fanfare, and her first few months in Bath were quiet. She accompanied Mrs. Dawson only twice to the Assembly Rooms. When by chance Mary learned that her friends the Ardens were living in Bath, she was eager to reunite with Jane Arden, whom Mary had met a decade prior when her family lived in Beverley in East Yorkshire. (Read about Mary’s early letters to Jane here, where I wrote a guest post for the Literary Ladies’ Tearoom.) It is Jane Arden whom we have to thank for saving Mary’s teenage writings for posterity.

Unfortunately, Jane was not in Bath. To her disappointment, when Mary visited the Ardens, they informed her Jane was working as a governess in Norfolk. Mr. and Mrs. Arden supplied Mary with Jane’s address, and the two girls, now young women, picked up a correspondence that had ceased upon Mary’s family moving to Hoxton in 1774.

Mary’s letters (she did not save Jane’s) show how glad she is to have reconnected with the Ardens that summer in 1779:

“You will, my dear girl, be as much surprised at receiving a letter from me, as I was at hearing, that your family resided at Bath; — I have been at this place two months yet chance never threw your sisters in my way — and if I had not by accident been informed of your father’s giving lectures, I might never have met with them. — As soon as I could enquire out their habitation I seized the first opportunity of paying my compliments to them: — my principle reason for doing so, was the hopes of seeing you…”[1]

But in letters to Jane that autumn, Mary is depressed, a chronic health condition she would battle her entire life. In becoming a companion, she has left the chaos of her dysfunctional home, but the outgoing Mary retreats from others as her life unfolds in Bath. “The more I see of the world, the more anxious I am to preserve my old friends, for I am now slower than ever in forming friendships…”[2]

Perhaps conscious of her poverty, Mary felt out of place in Bath, which was the height of fashion and parties. She comments to Jane on how vibrant the town is, but to her, it was nothing but balls and plays. “I am quite a piece of still life…” she writes,[3] then reminds Jane of her troubled home life. “It is almost needless to tell you that my father’s violent temper and extravagant turn of mind, was the principal cause of my unhappiness and that of the rest of the family.”[4]

Even now, she confides to Jane, her health suffers just remembering the difficult days of her childhood, how it festers in her still, calling it, “…a lingering sickness…my health is ruined, my spirits broken, and I have a constant pain in my side that is daily gaining ground on me: — My head aches with holding it down…”[5]

Despite her sadness, Mary also shares some of the good things that have happened in the half-dozen years since they last saw one another, an important one being meeting the Clares, “a Clergyman and his lady — a very amiable Couple…”[6] whom Mary met in Hoxton. They lived next door to the Wollstonecrafts on Queens Row, and their home became a safe harbor for Mary. She stayed with them sometimes for weeks. Mr. Clare opened his library and introduced Mary to famous Enlightenment texts while Mrs. Clare nursed her spirit.

The Clares also introduced Mary to Fanny Blood, “…a friend, whom I love better than all the world beside,” she writes to Jane, “a friend to whom I am bound by every tie of gratitude…”[7] A deep bond had formed between Mary and Fanny when they had met three years prior. Fanny’s family was as poor as Mary’s, and her father was as hapless a drunk as Mary’s. Mary relays in her letter to Jane that it is the height of her ambition to make a home with Fanny. She does not tell Jane that Fanny is engaged to Hugh Skeys, an Irish wine merchant conducting family business in Lisbon, Portugal. In Bath, being apart from Fanny most assuredly added to Mary’s forlorn state of mind. She thought Skeys not at all a serious suitor. Fanny was in the early stages of consumption. If Skeys loved Fanny, he’d not wait to make her his wife and ease the strain of poverty.

Things changed for Mary when, the following season, she visited Southampton with Mrs. Dawson and saw relatives from her mother’s side.[8] Mary gushes about it in a letter to Jane dated October 1780:

“I have spent a very agreeable summer, S[outhampto]n is a very pleasant place in every sense of the word — The situation is delightful; and, the inhabitants polite, and hospitable. I received so much civility that I left it with regret.”[9]

The vacation-like setting improved Mary’s health and outlook. Throughout her life, in fact, she would turn to nature for solace. And she seems to have warmed up to Mrs. Dawson by the end of the summer. Mary sees that she can benefit from her experience in a way that is important to her. In the same letter, she writes:

“The family I am here with is a very worthy one, Mrs. Dawson — has a very good understanding — and she has seen a great deal of the World, I hope to improve myself by her conversation, and I endeavor to render a circumstance (that was at first disagreeable,) useful to me.”[10]

Then, by spring 1781, Mary’s mood again plummets. In yet another letter to Jane, Mary writes:

“To say the truth, I am very indifferent as to the opinion of the world in general; — I wish to retire as much from it as possible — I am particularly sick of genteel life, as it is called; — the unmeaning civilities that I see every day practiced don’t agree with my temper; — I long for a little sincerity, and look forward with pleasure to the time when I shall lay aside all restraint…I don’t know which is the worst — to think too little or too much. — ’tis a difficult matter to draw the line, and keep clear of melancholy and thoughtlessness…”[11]

What, or whom, threw Mary off course in Bath just as she was beginning to settle into her circumstances? Mary’s biographers suggest it was a clergyman by the name of Joshua Waterhouse. In the same letter to Jane, Mary writes, “I really think it is best sometimes to be deceived — and to expect what we are never likely to meet with; — deluded by false hopes…”[12] Did Mary have had a flirtation with Waterhouse that left her disenchanted? No one is sure, but years later, her own words show up to suggest that she had.

There is no firm evidence of Mary having met Joshua Waterhouse in Bath. She never mentions him by name in her letters. But when one of Joshua Waterhouse’s servants murdered him in 1827, leaving him to bleed to death from a slit throat in a large brewing tub in the kitchen passage of his rectory, Waterhouse left behind a sack of letters he had amassed over his lifetime. The missives were mostly from women, including letters from one Mary Wollstonecraft.

Waterhouse was known to brag that he had enough love letters “to cook the marriage feast, whenever it should take place.”[13] He may not have been far off in his boastful comment. The following note regarding Waterhouse, who at the time of his death was the reclusive Rector of Stukeley, showed up in the newspapers:

“Among the numerous fair ones to whom the singular Rector of Stukeley paid his addresses, was the once famous Mary Wolstonecraft (sic), distinguished during the period of the French Revolution for her democratical writings…Several letters from the intellectual Amazon exist among the papers of the Rev. Gentleman.”[14]

It’s not only possible but probable that Mary met said gentleman in Bath. Guest registries indicate Waterhouse was in residence when Mary was there. A don from St. Catherine’s College in Cambridge and known as a lady’s man, Waterhouse visited Bath and other swank places with his rich friends. In an encounter, Mary would likely have found him appealing, given his looks and charm, and he was smart, educated. A farmer’s son, his humble beginnings were similar to Mary’s. She would have seen herself on even par with him in conversation, for Mary herself was bright and educated by mentors who gave her access to the kind of learning reserved for males.

According to one researcher, it’s Mary’s writing that hints at an affair with Waterhouse. In a passage in Thoughts on the Education of Daughters, Mary’s first advice book, she wrote:

“I am very far from thinking love irresistible, and not to be conquered…. I knew a woman very early in life warmly attached to an agreeable man, yet she saw his faults; his principles were unfixed, and his prodigal turn would have obliged her to have restrained every benevolent emotion of her heart. She exerted her influence to improve him, but in vain did she for years try to do it. Convinced of the impossibility, she determined not to marry him, though she was forced to encounter poverty and its attendants.”[15]

Were her cautionary thoughts based on Joshua Waterhouse? By all accounts, he was handsome and ambitious. And he was full of himself. Mary might have wanted to reform him, as she would try to improve her siblings in the future. Because she aspired toward self-improvement, she believed others should as well.

Another hint of Mary meeting Waterhouse is in her first novel, Mary, A Fiction, where she writes about a fictional unnamed gentleman as someone who comes to her heroine’s aid at the end of the book. When her heroine wishes to avoid her husband, she turns to this trusted friend whom she admires but knows is vain and undisciplined. Mary’s novel had many biographical elements; was she referring to Waterhouse?

Either way, Mary was wise to avoid an entanglement with him. When Waterhouse died, he’d turned into a miser. He blocked out his windows to avoid paying the window tax, and he stored wool and grain in his house. At one time, he had been engaged to marry and bought all new furniture, new clothes, and Turkish carpets, but the engagement was broken.

If Joshua Waterhouse’s affections or lack thereof were the source of Mary’s melancholy in the spring of 1781, we know her depressed mood didn’t last forever. As is common among the young, she bounced back quickly. In her last letter to Jane that summer, she seems at ease with herself. The possibility of her and Fanny living together has become more real. To Jane, she writes:

“I take up my pen again to tell you I have not for a long time been so well as I am at present. — The roses will bloom when there’s peace in the breast, and the prospect of living with my Fanny gladdens my heart…"[16]

After three years of working for Mrs. Dawson, Mary is finally happy. But her life soon takes yet another sudden turn. After writing to Jane, Mary is called home. Her mother, Elizabeth Wollstonecraft, is dying from dropsy. Mary returns the chaos and uncertainty of her youth to care for the woman who shunned her as a child.

In my next installment of Mary Wollstonecraft’s letters, read about what happens when, after Elizabeth Wollstonecraft dies, Mary’s sister Eliza marries a wealthy shipbuilder, and Mary is again called to the rescue.

All letter references are from The Collected Letters of Mary Wollstonecraft, edited by Janet Todd, 2003, Columbia University Press and printed in the original.

[1] Letter to Jane Arden from Mary Wollstonecraft, Bath, ?mid 1779, p. 19-20.

[2] Letter to Jane Arden from Mary Wollstonecraft, Bath, ?mid 1779, p. 20.

[3] Letter to Jane Arden from Mary Wollstonecraft, Bath, ?Christmas, 1779, p. 21.

[4] Letter to Jane Arden from Mary Wollstonecraft, Bath, ?early 1780, p. 23.

[5] ibid, p. 23.

[6] ibid, p. 24.

[7] ibid, p. 25.

[8] Todd, Janet. (2003) Mary Wollstonecraft: A Revolutionary Life. Columbia University Press. p 31.

[9] Letter to Jane Arden from Mary Wollstonecraft, Bath, October 17, ?1780, p. 17.

[10] Ibid, p. 27.

[11] Letter to Jane Arden from Mary Wollstonecraft, Windsor, ?April 1781, p. 28.

[12] Ibid, p. 29.

[13] Ibid, p. 165

[14] Nitchie, Elizabeth. An Early Suitor of Mary Wollstonecraft. PLMA, Vol. 58, No. 1 (March, 1943), pp. 163. Retrieved online from https://www.jstor.org/stable/459038.

[15] G.R. Stirling, quoted in Nitchie, Elizabeth. An Early Suitor of Mary Wollstonecraft. PLMA, Vol. 58, No. 1 (March, 1943), pp. 168. Retrieved online from https://www.jstor.org/stable/459038.

[16] Letter to Jane Arden from Mary Wollstonecraft, Windsor, ?late summer, 1781, p. 34.