Mary Wollstonecraft's Enduring Legacy

The Timeless Nature of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman

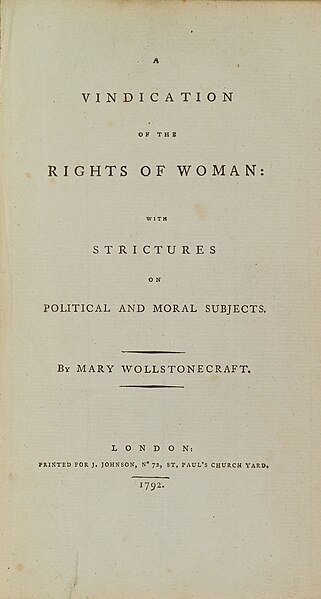

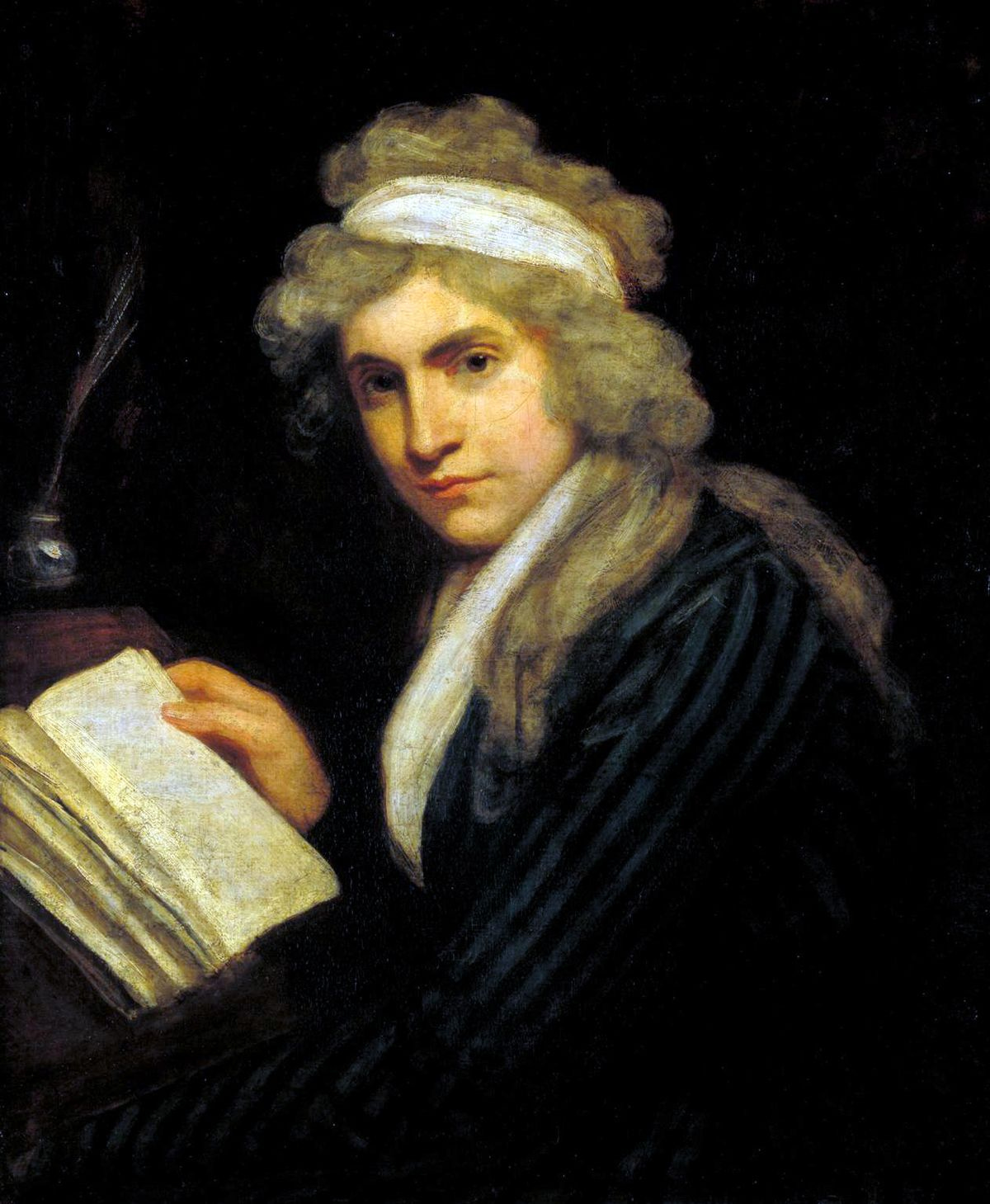

Women’s History Month would not be complete without a nod to Mary Wollstonecraft, the 18th century British writer and philosopher who in 1792 penned A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. Wollstonecraft is often referred to as the mother of feminism even though feminism as a word didn’t exist during her lifetime. Nor was she the first woman to write about the state of affairs for her sex. Yet her 233-year-old treatise continues to be held up as a source of profound political wisdom.

Wollstonecraft’s writing has a delightful zing to it. In A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, she didn’t hold back from chastising society in general and men in particular for keeping women “in the dark.” And she boldy linked her writing to the world’s stage at the time: the French Revolution.

The political landscape was in a state of rare change during the latter part of the 18th century. The age of oppressive regimes was beginning to show signs of crumbling, making way for modern democracies as citizens began challenging absolute monarchies and demanding liberty for the individual.

How different a theater than 2025 when far-right policies seem to be on the rise globally. Then, as now, economics were at play, though today cultural forces have added to people’s discontent, and according to this analysis from the Pew Research Center, people don’t see their democracies as functioning all that well. If alive, what would Mary Wollstonecraft say about the present shift in political winds?

Wollstonecraft was an unlikely candidate to rise to prominence in 1792. Though born into a genteel family, by the time she was a teen, her father had squandered the family fortune. Edward Wollstonecraft was also terribly abusive. At twelve, Mary would stand guard outside her mother’s bedroom in an effort to protect her from his violent outbursts. Believing all men held the potential to be tyrants behind closed doors like her father, she swore herself to spinsterhood.

Her determination to live singly, however, meant she would have to make her own way in the world, not an easy task for a middle-class woman in Georgian England. Work for genteel women was limited to being a companion, a teacher, or a governess, and one only stooped so low if one were poor. Think Jane Austen, who literary critics speculate was inspired by Wollstonecraft’s writing in penning Sense and Sensibility (1811).

But Mary Wollstonecraft was a pragmatist, and she worked in all three positions for a decade before deciding to become a writer. “I am then going to be the first of a new genus,” she wrote to her sister in 1787 shortly after she moved to London. “I tremble at the attempt yet if I fail—I only suffer…”

At the core of Wollstonecraft’s audacity was her brilliant mind. She’d been a student of the Enlightenment, having read radical works by the likes of John Locke, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and Voltaire, all of which prepared her well for the role she found herself in when she dipped her quill into the inkwell of political writing.

Her timing couldn’t have been better. Wollstonecraft’s enthusiasm for liberty and freedom for the individual coincided perfectly with what was happening at the time in France. The French Revolution was in full force. Commoners had toppled a monarchy, fanning the flames of discontent not just in France but throughout Europe on the heels of America winning its own War of Independence from Great Britain.

The very title of Wollstonecraft’s political treatise was a riff on France’s Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen. When the French Revolution broke out in 1789, Thomas Jefferson, America’s ambassador to France, helped Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette — yes, General Lafayette — write the initial draft of the declaration, which they based on America’s Declaration of Independence. Lafayette had fought alongside the colonists in the American Revolution and was close personally with George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison.

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman wasn’t Wollstonecraft’s first political piece. In 1790 she wrote A Vindication of the Rights of Men as a public response to Edmund Burke, an influential conservative member of Parliament who criticized the French Revolution in a lengthy political pamphlet. Burke saw the Revolution as ill-conceived. While he called the revolutionists “a swinish multitude,” Wollstonecraft defended them, asserting that personal liberty was a birthright, not an inheritance. The following year, Frenchwoman Olympe de Gouges wrote the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen, a direct challenge to France’s Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, which had excluded references to women. (Below: French woman during the Revolution in classical attire wearing a Phrygian hat by Jeanne-Louise Vallain)

Showing how truly clever she was, Mary Wollstonecraft structured A Vindication of the Rights of Woman as a response to Prince Talleyrand-Périgord, directly engaging the French politician charged with devising a new state-sponsored education system in France. Wollstonecraft lauded Talleyrand’s call for a free publicly funded education for boys and girls, but she departed with him when Talleyrand stood for perpetuating Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s proposition that girls’ education should be limited to preparing them for a life of subservience to men.

“I plead for my sex—not myself,” she wrote on page one of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. Truth must be common to all, she asserted, then asked Talleyrand why, in his educational plan, he left women out of reasoned conversation? On the following page, she wrote, “… if women are to be excluded from being granted the natural rights of mankind … this flaw in your NEW CONSTITUTION will ever show that man must, in some shape, act like a tyrant, and tyranny, in whatever part of society it rears its brazen front, will ever undermine morality.”

Wollstonecraft also called out women for being party to their diminished station by accepting, rather than questioning, the limitations society placed on them. “My own sex, I hope, will excuse me if I treat them like rational creatures, instead of flattering their fascinating graces, and viewing them as if they were in a state of perpetual childhood, unable to stand alone.”

Her goals were clear, however, and on the heels of her scolding she wrote, “I wish to persuade women to endeavor to acquire strength, both of mind and body, and to convince them that the soft phrases, susceptibility of heart, delicacy of sentiment, and refinement of taste, are almost synonymous with epithets of weakness…”

Wake up! she is saying to women, warning them that trivial attentions are forms of control in disguise. “How grossly do they [society] insult us who thus advise us only to render ourselves gentle, domestic brutes!”

Wollstonecraft wanted none of it. “Strengthen the female mind by enlarging it,” she wrote, “and there will be an end to blind obedience.” And later, perhaps her most famous line in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, “I do not wish them [women] to have power over men; but over themselves.”

Wollstonecraft’s treatise is filled with many more pithy quotes, underscoring her razor wit in filing her criticisms of society. A month after she published A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, Talleyrand visited her at her home in London, a courtesy suggesting her words resonated with him at least to some degree. It is said she served the prince wine in her mis-matched teacups. Wollstonecraft’s needs, lifestyle, and dress were plain. But she spoke and wrote with flair.

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman is revered in part for the role it has played long after Wollstonecraft’s death. The text inspired women’s suffrage movements in the 19th and 20th centuries on multiple continents and again, in the 20th century, during the second wave of feminism in the 1960s and 1970s. Today Wollstonecraft’s writing is still widely analyzed and debated in university settings for her views on equality and justice.

What would Mary Wollstonecraft say about current shifts in global politics? I believe she’d say don’t give up on democracy. Dictators, she would warn us, are no better than kings, that they are tyrants who feel no sense of duty, no moral obligation to their people. She would likely say to embrace Abraham Lincoln’s message of "government of the people, by the people, for the people." Government’s role, she would still insist, is to eliminate inequities in society and ensure no individual suffers poverty, degradation, or illness; that no one is left voiceless.

In 2026, America turns 250 years old. Building and maintaining a high-functioning representative democracy, as it turns out, is still a tall order. George Washington once reflected, “The establishment of our new Government seemed to be the last great experiment for promoting human happiness.” One can only hope the world’s beacon for representative democracy is not in its twilight. As global politics shift, it’s more important than ever for America to hold true to its founding principles. We can look to Mary Wollstonecraft to help shore up where we may be floundering and let her remind us that democracy, while messy, is worth it.

N.J. Mastro’s debut novel Solitary Walker: A Novel of Mary Wollstonecraft is biographical fiction about Wollstonecraft’s rise as a writer and philosopher and her ill-fated forays into love. Find it at online bookstores.

Brilliant essay. It feels like a blink in time that Mary Wollstonecraft’s sharp mind and voice took new ideas of freedom and elevated them to include women’s rights. Still so relevant today. She inspires me to keep on keeping on.